Melbourne in the fifties had a relatively small, predominantly white Anglo Saxon population which grew from 1,331,000 in 1950 to 1,850,000 in 1960. The average annual wage for an Australian male factory worker was 296 pounds three shillings and seven pence ($13,052.88). His female counterpart earned 146 pounds 18 shillings and four pence. A four pound loaf of bread cost eight pence and two pint bottles of milk (roughly equivalent to a litre) cost 11 pence.

Life in 1950s was still shadowed by the effects of WWII, but by the end of the decade deprivation was a distant memory. Melbourne was very parochial and considered itself the cultural and business capital of the country. Within it there were marked divisions between Catholic and Protestant as well as those who lived east of the Yarra and those to the west. Not as distinct but nevertheless significant was the divide created by the private schools. Despite the divides Melbourne society offered close networks. Cemeteries were an interesting example: they were divided into distinct denominational sections, and today it is possible to find families, who would have had affiliations with each other in the decades before the fifties, lying in close proximity in death.

Melbourne had boomed in the 1880s on the back of wealth from the gold rushes. It became known as Marvellous Melbourne with gracious public buildings and churches. Fortunately many of these survived for future generations despite major additions such as the huge glass towers behind the Rialto Towers, or changes in function for buildings such as the Elizabeth Street Post Office which has become a multi-functional building with limited postal facilities. The main activity in the city traditionally concentrated in the block bounded by Flinders, Lonsdale, Elizabeth and Russell Streets. Hoddle’s rectangular survey grid for the early city made it very easy for future generations to find their way around.

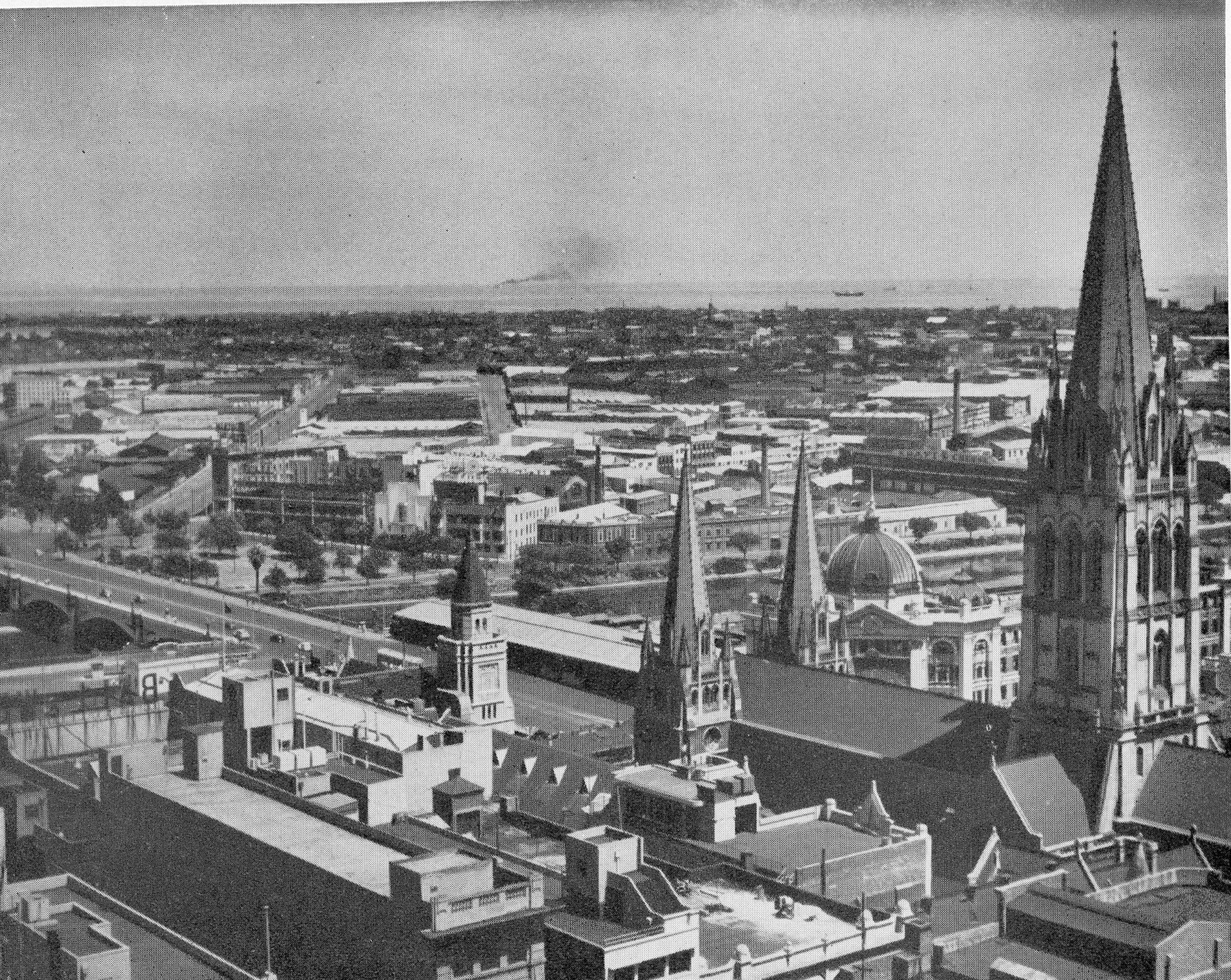

Melbourne’s skyline in the 50s was dominated by the spires of St Paul’s and St Patrick’s cathedrals, the Manchester Unity building, the Rialto building and Russell Street Police Station none of which exceeded sixteen stories. When the 20 storey ICI building was erected in East Melbourne in 1958 it was the tallest building in Australia.

Land was opening up for residential development in Williamstown, Bray Brook and Moreland in the west, McLeod and Templestowe in the north, and Ringwood, Mount Waverley and Frankston in the east.

City skyline, PMG radio collection

Melbourne’s skyline from the Yarra at the dawn of the 50s,

Photograph courtesy Jack Cato in his book ‘Melbourne’

By the fifties the city was serviced by excellent train services from all directions. Travellers still had the choice of first or second class and smoking or non-smoking. Some lines still ran with the ‘dog-boxes’ which provided small separate compartments with seats facing each other across the train. Each compartment had its individual door at each side of the train. Local lines terminated at Princes Bridge or Flinders Street stations and country trains came into Spencer Street station. Many of the local lines extended into rural areas and earlier generations of holiday makers had relied on them for their holidays to Ferntree Gully, Healesville and Warburton. The line to Port Melbourne and St. Kilda crossed the Yarra on the Sandhurst Bridge. It had been an important freight line from the warves, but this traffic ceased in the 50s and the line was eventually re-used as a light rail corridor in the 80s. Its route crossed the river at a different point and the bridge was dedicated to pedestrians and cyclists.

The city was also accessible by trams from the north, south, east and west; those from Wattle Park came in to the corner of Batman Avenue and St Kilda Road. This terminus was abolished along with Princes Bridge station when Federation Square was built. 1956 was a critical year for Melbourne tramways. Other cities were closing down their tram lines, but Robert Risson, the tramway commissioner, successfully campaigned not only to protect Melbourne’s system but also improve it.

Port Melbourne on Port Phillip Bay was the hub of international shipping. It was the disembarkation point for thousands of immigrants in the 50s. Traditionally wealthy Melbournians had left by ship to go back to the home country, but travel was almost impossible during the war years, and it was some time before Britain offered the incentives to make the long journey. By the mid-fifties however the lure of overseas travel was returning despite the weeks at sea and the expense which caused many cash strapped young people to take berths on freighters. Melbournians again went down to the warves to wave friends off or simply watch the drama of departures.

Dutch immigrants, Immigration Museum

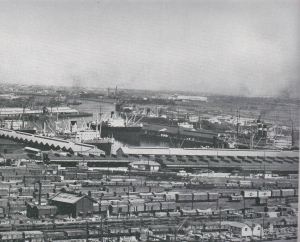

Melbourne had several eye-sores in its landscape. One was the ugliness of the Jolimont railway yards which spoilt the vista across Princes Bridge to Saint Paul’s cathedral. They were eventually covered by the development of Federation Square. Another eye sore was the tall brick shot tower which was somewhat at odds with its neighbouring building the State Library of Victoria. Although the tower persistently resisted demolition it was eventually disguised in the Melbourne Central shopping development. The docklands down on the lower reaches of the Yarra were also an eye-sore. In the early fifties Victoria Dock handled a large part of Victoria’s shipping cargo which could be directly offloaded onto goods trains passing through the freight terminal at nearby Spencer Street station. When containers came into vogue the demand dropped dramatically and the area became an embarrassment. However it was off the radar of most Melbournians unless they needed a warehouse. In due course the area was re-developed as the fashionable Dockland residential and business area.

Victoria Docks and goods trains.

Photo courtesy of Jack Cato in his book ‘Melbourne’

The site which became an immediate problem during the 1950s was Wirth’s Park located on the site in St. Kilda Road now occupied by the Art Gallery and Cultural Centre. Originally the site of a circus tent in 1877, the site developed as an entertainment centre. Wirths took it over in 1907 and built a large timber and galvanised iron building which was used for performances such as pantomimes when Wirth’s circus was on tour. The nearby Glaciarium skating rink was located on City Road but neighbouring sites were occupied by industries. When the Wirth’s building burned down in 1953 the area became a health and safety concern. The South Melbourne council approached the Melbourne City Council and National Gallery to consider the development of a cultural centre, but nothing was done for many years.

View to Hobson’s Bay across the Yarra

Photograph courtesy Rob Hillier in John Hetherington’s book ‘Portrait of Melbourne’.

Impressive public buildings have traditionally been a feature of the Melbourne landscape. One in particular deserves a mention. The Exhibition Building stands impressively in the leafy Carlton Gardens at 9 Nicholson Street.It was erected for the International Exhibition of 1880/1. At the beginning of the 1950s it had two wings, the west and the east which were originally the machine halls for the exhibition. The grand opening of the Federal Parliament was held in the west wing in 1901. This wing subsequently housed the Melbourne Aquarium, destroyed by fire in 1953. The east wing housed a ballroom, the Palais Royale, which was remodeled as the Royal Ballroom in 1952. The area between the two wings was originally used as a sports oval, but during the war accommodated Air Force personnel. Their barracks were converted to serve as a migrant reception centre from 1949 to 1962. Matriculation exams were conducted in the building during the 1950s and the Olympic weight lifting and basketball events were staged here in 1956. The building hosted regular motor exhibitions and home shows. An assortment of government services had offices in the wings. The east wing was demolished in 1979. After much public discussion, the building was restored and entrusted to the Melbourne Museum.

Exhibition Building

Photo courtesy of Museums Victoria

Shopping

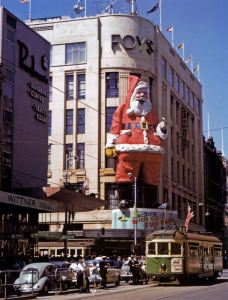

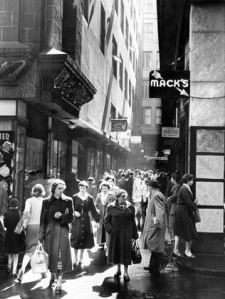

The cosmopolitan shopping was done in Bourke Street where Myer, Buckley and Nunn, and Foy and Gibson dominated trade, or in Flinders Street at the Mutual Store or Ball and Welch.

Foy and Gibson

Coles Variety store opened in Bourke Street in 1955 when Mantons closed. It provided for the lower end of the market offering haberdashery, clothes and odds and ends at extremely cheap prices.

Cole’s sale, Herald Sun Image Library

The large department stores ranged over multiple floors accessible by escalators or lifts which were manned by a uniformed person who announced the goods available on each floor. Sales attendants were attentive and kept a watchful eye on their counters where it was exciting to see a proliferation of goods after the deprivations of war time. The big department stores offered rest rooms for ladies providing toilets and comfortable chairs and mirrors where exhausted shoppers could put their feet up and repair the damage of their exertions. London Stores and Henry Bucks catered for men. Coles or Myers were the places to go if you wanted a cheap meal cafeteria style and Buckley and Nunn offered a dining room with waitresses in black with white aprons.

1952, Myer’s cafeteria, Herald Sun Image Library

By the end of the fifties a new breed of specialised stores appeared to meet the increasing demand for furniture, electrical and white goods. Waltons sold Melbournians lounge suites and Billy Gyatt tempted us with washing machines and kitchen appliances. The attraction of the big city stores dimmed with the growth of large suburban shopping centres in the 60s.

The exclusive shopping was done in the upper end of Collins Street where the department store, Georges, was the main attraction. A doorman in dress suit stood guard at the entrance, discouraging those not accustomed to paying the high prices for exclusive goods. Collins Street boasted boutiques offering wealthy Melbournians incredibly expensive clothes and jewellery. Le Louvre was typical of the high fashion boutiques which attracted wealthy ladies to this end of Melbourne. Founded by Lillian Wightman in 1922, it was Australia’s first Paris-style couture salon where shopping was by appointment only and clothes were brought from other rooms for consideration by the customer. Further up Collins Street were the premises of medical specialists, banks and large companies. This Spring Street end of Collins Street with gracious buildings and tree lined pavements was often referred to as the Paris end.

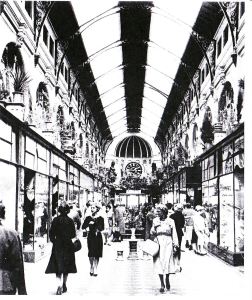

Melbourne was distinctive because of its arcades and laneways. It offered opportunities to discover exciting retail opportunities hidden within the major city grid. There were three particularly popular arcades, two of which have continued to enthral shoppers. The Royal Arcade, which connects Bourke and Little Collins Streets, features the figures of Gog and Magog who have been striking the hour for generations. The Block Arcade with its beautiful glass ceilings takes you from Little Collins through to Collins or Elizabeth Streets. The famous Australia Arcade in Collins Street took you through shops to the Australia Hotel. It lost its enchantment when it became the Australia shopping precinct in 1989 following the demolition of the hotel.

Gog and Magog, Royal Arcade

Photo courtesy Joan Beddoe

Royal Arcade,

Photograph courtesy Gordon De Lisle, ‘Melbourne+Big+Rich+Beautiful’

Centreway Arcade, Herald Sun Image Library

Block Arcade

Photos courtesy Joan Beddoe

Myers windows were specially decorated for Christmas for the first time in 1956. This established a tradition which has continued to draw huge crowds every year.

Flinders Lane was the hub of the fashion industry with fabric warehouses and ancillary manufacturers servicing the design houses. It had developed very early in Melbourne’s history because of its proximity to the river and railway. By the 50s the buildings and services were becoming antiquated, but that was regarded as part of the mystique of the Lane. Many of the businesses were set up by Jewish entrepreneurs, and as they aged, their businesses would close, so the fifties would prove to be the last of the glory years for the rag trade in Flinders Lane.

The prominence of retail in Melbourne life in the 50s can be partly attributed to the Jewish community. Many Jewish people emigrated from Eastern Europe just before and after WWII and Melbourne was reputed to have the largest community of holocaust survivors anywhere in the world. However there was a well-established Jewish community living in Melbourne well before WWII. The early immigrants were mainly of western European origin and more liberal in their outlook than the later arrivals from Eastern Europe. Many Jewish families congregated in the suburbs between Caulfield and St Kilda and many achieved great wealth although they had arrived with very little. For example the Smorgan brothers who had arrived in Melbourne in 1927 established a butchery which grew into the full scale meat works: it dominated the small goods industry in the 50s. Others made fortunes in clothing manufacture and retail.

The Victoria market at the far end of Elizabeth Street was the wholesale outlet for food produce. Melbournians did not go there to do their weekly shop because they were on first name terms with their local suburban butcher, grocer and fruiterer, and often preferred them to the slowly emerging self-service groceries.

1950 grocery store, Herald Sun Image Library

They were yet to witness the opening of Melbourne’s first free standing integrated shopping mall at Chadstone in October 1960 which heralded in a major change in Melbourne’s shopping habits.

Another interesting feature of Melbourne as a city was the attraction of certain local suburban shopping strips. Carlton’s Lygon Street and St Kilda’s Acland and Fitzroy Streets had traditionally attracted locals and visitors, along with Smith Street Collingwood, Sydney Road Brunswick, and Bridge Road Richmond, but in the 50s Toorak Road was becoming popular. Hotels were a major attraction but they were tarnished by the six o’clock swill caused by the prohibition of sales of alcohol after six.

Moonee Ponds, Herald Sun Image Library

Sporting Venues

Melbourne Cricket Ground

The MCG was established on the corner of Brunton Avenue and Punt Road in 1853. In the years since it has been at the centre of Melbourne’s passion for cricket and Australian Rules football. It hosts the traditional Boxing Day test match when a series is played in Australia, and traditionally holds the finals of the football season. It accommodates large outdoor events and in 1956 it was the obvious venue for the Olympic Games. In the 1950s the ground was administered by the Melbourne Cricket Club (MCC) under the control of trustees appointed by the state government. The MCC auspiced a wide range of sports including baseball, croquet and golf although only tennis and bowls were located in the vicinity of the MCG.

Over the years sporting memorabilia had accumulated, and in the 1950s the Baillie collection was acquired with 200 cricket works from prominent sporting journalists. As a result the library was re-organised under the supervision of an honorary librarian.

During the 50s the schedule for test matches was extended to include the West Indies, Pakistan, South Africa and India as well as the traditional foe, England. During the decade Australia won 28 out of 57 matches and 15 were declared a draw. A popular batsman was Neil Harvey who averaged 50.25 runs per innings with a career total of 4573, and the most popular bowler was Richie Benaud who took 165 wickets at an average of 23.95.

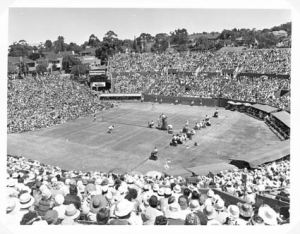

Kooyong Tennis Centre

Built in 1927 in Glenferrie Road, Kooyong, the centre has been the venue for Davis Cup and Australian Open tournaments. The highlight of summers in the fifties was the Davis Cup, the international tennis competition which Australia and the US dominated until 1973. Australia took the cup each year during the decade except in 1954 and 1958. Frank Sedgeman, Ken Rosewall, Lew Hoad, Ashley Cooper, Malcolm Anderson and Ken McGregor were tennis heroes. Sedgeman, Hoad, Cooper and Anderson all won Grand Slam titles.

Kooyong Tennis Centre, Herald Sun Image Library

Festival Hall

Wrestling and boxing were popular sports in the 1950s. Matches were staged in suburban venues, but major events were held at the West Melbourne stadium. The building burned down in the mid-fifties and was re-built, opening as Festival Hall in 1956 in time for the Olympic Games. It then hosted large concerts as well as sporting events.

Racecourses

Horse racing, has been an essential element of life in Melbourne since its foundation. The city boasts three major racecourses, Flemington, Moonee Valley and Caulfield. The Argus newspaper of Saturday August 5, 1951, advised readers that 43 special trams would run from the Elizabeth Street terminus to Moonee Valley for race patrons.

Flemington’s Melbourne Cup, has attracted enormous crowds since the first event in 1861. The day was reserved as a public holiday as early as 1877. Rising Fast, who won the Melbourne Cup in 1954, was a particular favourite with the public.

Dining Out

Dining out was usually reserved for very special occasions during the 50s. Popular, and often expensive restaurants in South Yarra included Maxim’s, the Volga Volga, and Hermes Cabaret restaurant. Drossou’s in Lonsdale Street and Ricco’s in Spring Street were two of the very few licensed venues.

Melbourne had a long history of coffee lounges. Coffee houses serving percolated coffee had proliferated in the gold rush period of the 1850s and by the 1950s cafes such as Gibby’s, Cafe Mozart, Russell Collins and Elizabeth Collins were popular.

Italian and Greek cafes and eateries were making their mark and became more acceptable to Melbournians after the Olympic Games introduced an international flavour to the city. Pellegrini’s in Bourke Street, Mirka cafe in Exhibition Street, Mario’s in Brunswick, and The Gallion in St Kilda were all established by post-war immigrants. The Italians cemented the tradition of coffee drinking in the Melbourne culture. In 1953 the Gaggia espresso machine arrived in Melbourne and was installed in the Il Cappuccino café in St Kida the following year. It soon appeared in the University Café in Lygon Street and Pellegrini’s in Bourke Street.

Pellegrinis 2016

Photo courtesy Joan Beddoe

The sidewalk Café, Melbourne’s first kerb-side café was opened in the Oriental Hotel in 1958 and, although police closed it down after two years because it blocked the pavement, Melbournians were warming to the idea of outdoor dining.

The Olympic games provided an impetus for more varied dining experiences. The Herald Saturday Jan 5, 1957 commented: ‘Interstate visitors have long been accustomed to describing Melbourne as a city lacking in nightlife, but if the new restaurants and cabarets springing up are any indication, it will soon have a surfeit of such places. The latest venture in this field is “The Green Dolphin,” close to the city at 323 Smith St., Collingwood. Owned and operated by MARIO … the entire place has been designed like a ship with an upper deck, portholes, seascapes on the walls, and a really nautical atmosphere throughout…A first-class quintet, led by trumpet star CLIFF REECE, plays for dancing every night, and Mario has secured one of the top Olympic chefs to head an all-star culinary line-up. He is Luigi, who cooked for the Italians and South Americans, two Latin races famous for their gastronomical discrimination. If the opening night was any indication, the place deserves to be a great success. There appears to be a steady flow of performers coming to Australia from the East these days’.

At the end of the decade the number of Chinese restaurants began to increase in response to the relaxation of immigration laws for non-English speaking people.

Manufacturing

Melbourne was traditionally recognised as the manufacturing capital of Australia. The inner suburbs bristled with steel companies, small engineering shops, clothing and shoe manufacturers, food processors, and paper and packaging industries; Ford cars were manufactured at Geelong and Holdens at Fisherman’s Bend. The local manufacturing industry had been vital during the war years when Australia was isolated from overseas supplies. They provided work for apprentices and eager school leavers who had no trouble finding a job.

Housing

When Menzies’ Liberal government came to power in 1949, the rationing of building materials was lifted. Up to that point the Labor government had concentrated building efforts on public housing to make up for wartime shortages. So in the fifties Melbournians witnessed the rise of building companies such as AV Jennings who caught the public imagination with cream brick triple fronted houses with steel window frames in cream, green or blue.

The poor standard of housing in the inner suburbs was gaining attention in the 1950s. Some homes had no running water or adequate sanitation. They attracted tenants who could only afford minimum rents.

North Melbourne, Herald Sun Image Library

As people moved out into new housing commission homes, Greek and Italian migrants took their place often buying the houses to renovate. Many houses were demolished, but public pressure fortunately saved some areas which have subsequently become gentrified.

The housing shortage of the 40s and 50s was being addressed by the Housing Commission which operated from a large new factory at Homesglen, producing ready to assemble pre-cast concrete slabs: it produced 951 houses in 1951 alone.

New estates opened in Jordanville, East Dandenong and Northcote.

Housing Commission house, Victorian Department of Human Services

Three storey blocks of flats went up in North Melbourne, Northcote, Hawthorn and Coburg. The Olympic Village in Heidelberg converted to public housing after the games in 1956. Unfortunately the concentration of people on low incomes created social problems.

Problems also arose in some migrant hostels which were hurriedly organised to meet the demands of post-war migration. Migrants were given accommodation for twelve months after their arrival. Most hostels were Nissen and Quonset huts, prototype buildings, army huts or converted wool stores built in the 1940s. They could be found in Altona, Broadmeadows, Brooklyn, Fishermans Bend, Holmesglen, Maribyrnong, Nunawadding and Preston. Facilities were very basic with communal bathrooms, laundries and kitchens. There was widespread dissatisfaction in response to the rent which could absorb 80% of a migrant family’s income. Disaffected youth often formed groups such as the notorious Broady Boys of Broadmeadows.

Art World

The National Gallery of Victoria was the centre of the artistic world in Melbourne in the 1950s when it was housed in a wing of the State Library building. Founded in 1861 it was Australia’s oldest art collection and has always been a major attraction to Melbournians and visitors alike. The National Gallery of Victoria Art School founded in 1867 produced some of Australia’s best known artists. However in the 1950s there were other influences at work in the art world. Sunday and John Reed, had welcomed artists to their home, Heide, in Bulleen since 1934. They were both friends and patrons of Sydney Nolan, Albert Tucker, Joy Hester and John Percival. They also had a close association with artist Mirka Mora and her husband George who arrived from France in 1951. The Moras settled in an apartment at Grosvenor House, in Collins Street where many artists had their studios. With the support of the Reeds and Moras the Contemporary Art Society was revived with its Gallery of Contemporary Art. This became the Museum of Modern Art of Australia in 1958, displaying the Reed’s extensive art collection. John Reed who was a lawyer, art editor and collector as well as publisher, was in a strong position to promote the artists of the 1950s. Charles Blackman, Arthur Boyd, David Boyd, John Brack, Robert Dickerson, John Perceval and Clifton Pugh, who belonged to the Contemporary Art Society, became the group known as the Antipodeans, a name suggested by Bernard Smith, art historian at Melbourne University who took a strong interest their work. He drew up the manifesto which accompanied the Antipodeans’ exhibition at the Victorian Art Society in 1959. The exhibition was staged to promote the tradition of figurative modern art as opposed to geometric abstract work which was growing in popularity, particularly in Sydney. The Boyd family meanwhile had been making their mark on the Australian art scene. Merric Boyd had built a small studio and home on the land his parents purchased for him in Murrumbeena in 1934. He established a reputation as a sculptor His children and their families lived on the property for many years, with his son Arthur being the last to leave. Arthur set up the Andrew Merric Boyd studio in Neerim Road Murrumbeena in 1943 along with John Percival and Peter Herbst. It closed in 1958, a year before Merric died.

Entertainment

Films

Melbourne had a long history of theatre patronage. The Regent in Collins Street and the State Theatre in Flinders Street were particularly ornate. The Regent theatre, which opened in 1929, had been built in opulent Spanish Gothic and French Renaissance styles to seat 3,500 patrons. After a fire it re-opened in 1949 complete with its ornately decorated dome and organ which rose from the orchestra pit. It screened the first Cinemascope film in 1953. This required a curved screen which was over fifteen metres wide installed over the orchestra pit. The theatre closed in 1970. Below the Regent was the Plaza Cinema, originally designed as a ballroom. It showed the first Cinerama processed film in 1958 using a giant curved screen and three projectors. The State Theatre was built in 1929 complete with minarets and towers, decorative windows, and a ceiling decorated with constellations of the night sky. Seating 3,371 people, it was the largest in the southern hemisphere. At the end of the fifties it was reconfigured into two theatres and renamed the Forum. The Capitol Theatre in Swanston Street opened in 1924. It was designed by Walter Burley Griffin and his wife Marion. Its Wurlitzer organ played until the mid-fifties. The ceiling was designed to resemble crystals and lit up in changing colours. Less extravagant theatres were the Metro in Burke Street and Savoy in Exhibition Street. There were also small movie theatres dedicated to newsreels which would be repeated throughout the day and into the night. Covering major events and topics of interest, they played an important role before the arrival of television.

State Theatre, corner Russell and Flinders Streets,

Photograph courtesy Jack Cato in his book ‘Melbourne’.

Picture theatres had large foyers with ticket offices, but no confectionery or drinks were sold here. Screenings usually began with a newsreel or shorts followed by a film, then an interval and another film. Patrons were shown to their seats by usherettes equipped with torches, and at interval you could purchase drinks, ice-cream and lollies from the eager young man roving the aisles. Deborah Kerr and Cary Grant filled the screens with ‘An Affair to Remember’, Marlon Brando with ‘A Street Car Named Desire’, and James Dean in ‘East of Eden’. The most notable Australian film was ‘Jedda’ (1955) and the most internationally recognised Australian actors were Chips Rafferty and Peter Finch.

Cinemas were located in most major suburban shopping centres. The Saturday matinees were well patronised by local children keen to see their favourite cartoons screened before the feature film. Visits to the movies changed dramatically in 1954 when the ‘Skyline’ drive-in theatre opened in Burwood in Melbourne. It was the first of 300 built around Australia.

Despite the attraction of colour feature films, the advent of television heralded the decline of cinemas in Melbourne. It was estimated that attendances dropped by 5 million in 1957, ticket sales in 1961 were only 52% of those in 1956, and 33% of Melbourne cinemas had closed by 1959. The resurgence of film attendance later in the 60s saw the emergence of very different cinemas.

Film societies and film nights were popular. Community groups and individuals could borrow documentary and feature films from the Victorian State Film Centre opened in 1946 at 110 Victoria Street Carlton. The centre had its own delivery vans which serviced regional towns and sent mobile projection units to visit outlying areas. Melbourne locals could collect and return films at the well-staffed film library office. Functions of the centre included repair of damaged films and archiving of Australian produced films including The Sentimental Bloke and On Our Selection. Documentary, educational, and feature films were being produced in the 50s by the Waterside Workers’ Film Unit (1952-1958), the Shell Company Film Unit, the Department of the Interior Film Division, and the Film and Television Production Association formed in 1956.

The popularity of film societies gave birth to film festivals. The Federation of Victorian Film Societies hosted a film festival at Olinda in 1952 and this led to the staging of the Melbourne Film Festival at the Exhibition Building the following year. The Australian Film Institute was founded in 1958 with government and corporate assistance , and that year commenced the presentation of awards at the Melbourne Film Festival. Melbourne is renowned for its annual film festival.

Live Theatre

Melbourne’s tradition of live theatre continued to blossom in the 50s. The four main theatres were Her Majesty’s in Exhibition Street, the Princess Theatre in Spring Street, the Tivoli in Bourke Street and the Comedy Theatre in Exhibition Street. Her Majesty’s, which opened in 1886 as the Alexandra Theatre, was renamed in honour of Queen Victoria. James Cassius Williamson, an American theatre producer, took over the building in 1900 and renovated it. Performing artists included Dame Nellie Melba and Anna Pavlova. In the 50s live shows included Call Me Madam, 1953; Paint Your Wagon, 1954; Can-Can, 195;, The Boy Friend, 1956; The Pyjama Game, 1957; Damn Yankees, 1958; My Fair Lady 1959. (Original Australian Production).

The site of the Princess Theatre staged entertainment as far back as 1854. Garnett H Carroll took control of the theatre in 1952 and presented opera, ballet, musical comedy and drama, including The Tales of Hoffmann for Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip who visited in 1954. The Vienna Boys’ Choir performed in 1954 and the Chinese Classical Theatre in 1956. American musicals were a favourite with Melbourne audiences and these included Kismet produced by Garnett Carroll in 1954.

The Tivoli replaced an original theatre, the Opera House. It was remodelled in 1956 to provide 1,442 seats on three levels. It continued the tradition of vaudeville performance, re-opening with Olympic Follies in reference to the Olympic Games staged in Melbourne that year. Many international stars performed at the theatre before it closed to become a picture theatre in 1966. The following year it was damaged by fire and was demolished.

The Comedy Theatre was built in 1928 with a Florentine style façade on the site of the 1850s “Iron Pot’ which was Melbourne’s earliest play-house. Productions staged during the 1950s included A Street Car Named Desire, Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, and A Shifting Heart.

Student reviews at Melbourne and Sydney universities were training grounds for many aspiring actors, producers and directors. Melbourne University’s Union Repertory Theatre nurtured Australian writers and actors. It became the Melbourne Theatre Company in 1953, the first of Australia’s professional theatre companies. The Union Theatre provided the stage for the premier of Ray Lawler’s ‘Summer of the Seventeenth Doll’ in 1955 reminding Australian audiences that Queensland sugar cane cutters could be a source of inspiration. Barry Humphries materialised as Edna Everidge on the same stage that same year.

The show Out of the Dark was performed at the Princess Theatre in 1951. Unfortunately a program and a few black and white photographs were all that survived to remind later generations. It was commemorated in an exhibition at the City Gallery Melbourne Town Hall in 2008. Out of the Dark featured dancing, singing, fire, snake handling, and boomerangs flying through the auditorium over the heads of the audience. It was the brain child of Doug Nicholls who was appalled at the lack of Aboriginal content in the Victorian centenary celebrations. Under the direction of Aboriginal activist, showman and entrepreneur, Bill Onus, a cast was assembled from Melbourne, New South Wales and Queensland Aboriginal communities. It included opera singer, Harold Blair, and cabaret artist, Georgia Lee. The show attracted 12,000 people to five shows. Unfortunately plans for a tour did not eventuate.

Dances

The social life of most young people in 1950’s Melbourne centred around the Saturday night dances. In the early 50s dances were prescriptive: Pride of Erin, fox trot, barn dance and such, all followed by the compulsory waltz at the end of the night. It was expected that the band would play Lullaby of Birdland and When the Saints Go Marching In at some point in the evening. Men and women often congregated separately with the women seated around the walls and the men clustered at one end before venturing out when the music started to invite a woman to dance. Venues included church halls, town halls or sports clubs. Town hall dances attracted the largest crowds and could provide professional big bands. Syd Palmer’s band played on Saturday and Wednesday nights at the Heidelberg Town Hall to crowds of 1000 dancers.

Photograph courtesy of Gary Palmer

The Power House Rowing Club in Albert Park was very popular in the late 50s and provided for less formal dancing under dim lighting. Ormond Hall in St. Kilda Road was a more exclusive but very popular venue. Jazz, swing or Dixieland bands with an emphasis on saxophones maintained the energetic atmosphere in all venues.

American square dancing arrived in the early 50s and invaded ballrooms as well as local halls. The music and movements directed by callers was prescriptive. Dancers could join clubs or buy records to dance informally. After the release of the film Blackboard Jungle in 1956, rock and roll dancing became popular. It was no longer necessary to have physical contact with a partner and the tradition of a man inviting a woman to dance was no longer necessary. The experience of going to a dance on Saturday night was waning by the end of the 50s when the lure of TV and the drive-in theatre proved to be stiff competition.

The 50s was a decade of formal celebrations for community groups, businesses and families. Weddings and 21st birthdays were cause for major family celebration, often held at formal reception venues. Many of these were stately mansions originally built as family homes incorporating ballrooms. One of these was Tudor Court, a mansion in Kooyong Road Caulfield originally completed for private owners in 1908. During the fifties it served as a reception centre where revelers danced in the ballroom late into the night. The property was sold to a developer in 2007 and demolished. Another popular venue was 9 Darling Street in South Yarra, also a stately mansion, which was subsequently demolished to make way for apartments, although a reception venue continued to operate there. Butleigh Wooton in Kew survived as a reception centre from 1939 until 2016. The two storied Italianate style mansion was completed as a private home in 1885 and resumed that role in 2016. Celebrations have continued to be held at The Gables in Malvern. This Victorian style home with gracious verandahs has 15 rooms and an acre of gardens featuring trees over 100 years old. Balls were often held there during the 50s.

Balls were very popular during the 50s, and many young girls took often reluctant partners through the process of the debutante ball, in keeping with the long out-dated tradition of being accepted into society. Large ballrooms were a feature of Melbourne and the popular ones in the fifties included the Palais de Dance and Earls Court on the Esplanade, St. Kilda, Leggets in Prahran, the Railway Institute ballroom above Flinders Street station and the Royale Ballroom in the Exhibition Building, Carlton.

The Palais de Dance was built next to the Palais Theatre in 1919. The interior designed by Walter Burleigh Griffin and his wife Marion provided seating behind Doric type columns surrounding the dance floor. The ceiling featured a pattern of prisms which were lit for special effect. Louvered wall panels could be hinged open to allow the sea breezes to flow through the building. The building had a capacity for 2,750 dancers. It was destroyed by fire in 1969.

Earls Court was located on the St.Kilda Esplanade next to the St. Moritz ice skating rink and opposite the Palais de Dance. It was built in 1927 and originally served as a picture theatre before converting to a three floor dance venue. The façade was embellished with square towers and emblem shields. It adopted various names as music venue and night club before it closed in 1985.

Leggetts Ballroom opened next to the Prahran station in 1920 and was destroyed by fire in 1976. In its hey-day it had a capacity for 6000 dancers and employed as many as 100 instructors for dancing lessons. It operated six days and nights a week with a variety of themes for particular nights. The huge dance floor had a stage at each end which allowed two bands to play for the one occasion.

Crowds flocked to the ballroom on the third floor of the Flinders Street station in the 50s. Originally the lecture hall of the Victorian Railway Institute, the area was closed to the public in 1985 because of its state of disrepair.

The Royale Ballroom opened in 1952 of the eastern annexe of the Exhibition Building facing Nicholson Street. It was popular for local dances and balls during the 50s .

Melbourne’s night life was hampered by strict licensing laws which prohibited the sale of alcohol after 6.p.m and all day Sunday. The licensing squad often fined venue proprietors for allowing undercover sales or illicit smuggling by patrons. Night clubs came and went during the 50s: Claridge’s in South Yarra became the Embers and survived into the 60s despite a fire and a bomb blast; Robert Maas, an Austrian immigrant converted his café in High Street St. Kilda into the Maas Cabaret; the Moulin Rouge in Dickens Street, Elwood, survived from 1954 to 1956; and Ciros which opened in 1948 morphed from a night club to a restaurant, a reception centre, to a cabaret venue. Most night clubs served meals, either as a dinner session or a supper session.

Dancers at Ormond Hall, Herald Sun Image Library

Other Leisure Activities

Social events organised by churches or community groups such as the Red Cross and CWA would get older Melbournians and families out of the house. There was always an emphasis on food, and often this involved taking a plate for afternoon tea or supper. Entertainment at these events was often provided by soloists and pianists. There was no shortage of clubs for children, in particular scouts, guides and church groups, which varied in degree from teaching useful skills to pure fun and games. After the intensity of working for causes during the war years, people were happy to devote their community spirit to enjoyment. Local tennis and cricket clubs were well patronised by adults and children, and more affluent folk could afford the indulgence of golf clubs. Free municipal libraries were only just beginning to multiply sufficiently to be accessible to local families. The Moomba Festival was launched on March 1st 1955 with the now traditional parade.

Travel

Only wealthy Melbournians considered travel by plane. The leading airlines were Ansett and TAA with booking offices in Swanston Street. All domestic and international flights came into Essendon airport which originated as a site of an aero club in 1919. It became an official airport in 1921 and was used by the defence forces in WWII. It was officially declared Melbourne’s international airport in 1950. Even by the mid-fifties it was becoming inadequate for the number of passengers and improving jet aircraft. The new Tullamarine airport opened in 1970 and Essendon continued to service lighter traffic.

Those who could not afford the expense of domestic flights travelled by bus or train. All interstate trains left from Spencer Street. The trip to Sydney involved a change of trains at Albury because New South Wales tracks were a different gauge. It was common for trains on this route to be pulled by steam locomotives.